No New Information

UNC has been arguing that, as far as NCAA bylaws are concerned, the findings of the Wainstein Report didn't result in any "new information" that wasn't already known to NCAA investigators when the academic misconduct was first uncovered in August-September 2011. From that early point in the UNC academic scandal, and up until the Wainstein investigation, NCAA enforcement staff had been affirming to UNC that the discovered misconduct had violated no NCAA rules.

In the dialogue between the NCAA and UNC over allegations issued since the Wainstein Report, NCAA Enforcement has been saying that Wainstein's investigation did, in fact, offer substantially new information; enough so to warrant issuance of a new set of bylaw infraction allegations. UNC's defense team begs to differ.

Though UNC is working to paint the picture otherwise, UNC's administration has acknowledged the difference Wainstein made by its words and by its actions. NCAA Enforcement has cited those actions in response to UNC's objections, but UNC has tried to explain the distinctions between what guided the institution's response and the NCAA's jurisdiction.

I agree with Enforcement Director Tom Hosty. UNC acknowledged and treated Wainstein as having revealed new information, some of which is pertinent to NCAA bylaws infractions.

Words

For one, the Wainstein Report was sufficient to move UNC's accreditation agency, Commission on Colleges of the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools (SACSCOC) to reopen its case and ultimately serve the institution with probationary notice; a first for a tier-one university. SACS had conducted visits and had access to UNC-endorsed reviews (Hartlyn-Andrews and Martin Report). Yet SACS cleared UNC.

SACS was stern after Wainstein, noting that the curricular "irregularities" outlined in the Wainstein Report had constituted "academic fraud" and that the academic support program for athletes had played a role in the systemic failure to "control athletics." It was the "new information" of Wainstein that led SACS to place UNC on probation.

UNC has tried to reconcile its conciliatory response to SACS with its contention of issues before the NCAA. I'll save my challenge to that segregation attempt for another time, but the NCAA has refused to accept UNC arguments in that regard as well.

Actions

For this article, I'd like to focus on the fact that UNC made several personnel employment decisions on the basis of Wainstein's findings that were not deemed warranted prior to his investigation. Employee terminations included four individuals who had worked for the Athletics Support Staff for Student-Athletes (ASPSA). But when NCAA Director of Enforcement, Tom Hosty, noted this, UNC's legal team of Bond, Schoeneck & King (BSK) responded:

|

| January 7th, 2016: Rick Evrard to Tom Hosty |

This Evrard-Hosty dialogue occurred in December 2015 to January 2016, and the two were referring to the May 2015 Notice of Allegations (NOA). It is relevant today because the third version of the NOA has restored the pertinent allegations of the first, resurrecting the debate.

I want to look at this and test Mr. Evrard's claim that it is incorrect to deduce a nexus between UNC's firing of academic counselors to athletes and the conduct of those counselors asserted in the NCAA allegations.

Counselor Conduct Cited in Notice of Allegations No. 1

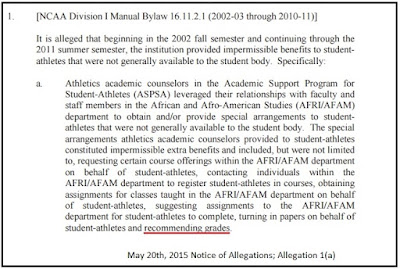

The original Notice of Allegation and the 2nd Amended NOA (third version) assert in Allegation 1 that ASPSA counselors had leveraged relationships with AFAM faculty/staff to obtain/provide special arrangements for student-athletes.

One example the NOA gives of such conduct was counselors "recommending grades."

|

| http://carolinacommitment.unc.edu/files/2015/06/NCAA-NOA.pdf |

UNC's Rationale for Personnel Action Post-Wainstein

It's difficult to dispute or validate Evrard's claim since the University of North Carolina has not (to my knowledge) ever provided the public with a rationale for the terminations of the three at-will counselors: Beth Bridger, Jaimie Lee and Brent Blanton.

But the termination letter for Jan Boxill was made public; and it plainly states the termination action was based on "heretofore unknown detail" and evidence of Boxill's misconduct, which specifically includes one of the conduct elements outlined in Allegation 1. The termination letter language is actually more severe, citing "requesting grades" vice "recommending grades" as NCAA Allegation 1 states:

|

| https://drive.google.com/open?id=0B24WwCUVnfYtVXlVVmpBQWhjdnM |

Assessment of the UNC/NCAA Enforcement's Dispute Over "Now New Information"

Clearly, for Boxill at least, termination was not merely for violations of University policy that were separate and distinct from conduct NCAA cited in the NOA. The University's rationale may not mirror, verbatim, the articulation of conduct in Allegation, but it strains belief to deny that the institution's employment actions were NOT "based on new information that the institution learned about the conduct asserted in Allegation 1(a)" as Rick Evrard claims.Of the four terminated who were academic counselors to athletes (Boxill, Bridger, Blanton and Lee), we only have the expressed reasons for UNC's actions in Boxill's case. The termination letters for the other three were not required to explain reasons for termination since they were at-will employees. However, the university is supposed to provide a public rationale after those employees appeal processes have been completed.

I'm unaware if UNC ever did release the rationale in any of the termination decisions of Bridger, Blanton or Lee. If Rick Evrard has this information, the University should make that public (and I would expect it to be dated prior to the communications between UNC and NCAA Enforcement cited above).

Boxill's case, in any regard, disputes Evrard's rebuttal of Hosty.

Epilogue and Current Status

NCAA Enforcement staff had noted the discrepancy between UNC's defense claim of "no new information" and the SACS probation/employee termination rationale during discussions and debate over the first version of the Notice of Allegations.The NCAA staff did appear to concede to UNC's late-2015 arguments when it removed the "special arrangements" language and the whole of Allegation 1(a) when issuing the April 25th, 2016 Amended Notice of Allegations. But after the guidance and opportunity afforded by the Committee on Infractions in November 2016, the Enforcement staff reversed that change and the allegation was restored in the December 13th, 2nd Amended Notice of Allegations.

UNC has objected to this reversal on multiple grounds, but must now re-engage the "no new information" argument that it thought it had already decisively won. The complaint has now been added to the litany of alleged Enforcement staff and Committee on Infractions protocol violations.

Since the NCAA's current case hinges on the "new information" that came from Wainstein's investigation, we can expect this and other assaults on the Wainstein Report to, again, be at the core of the University's retort (and that of partisan media outlets looking to support UNC's "narrative.")

Note: Portions of this article have been incorporated from an earlier blog posted on January 19th, 2017.