"Is this academic fraud? Yes, it is by a normal person's standards. But by the NCAA definition [it is not]."What IS the NCAA's definition of "academic fraud?"

Is the NCAA even charging UNC with "academic fraud?" After all, the words don't appear in any of the allegations.

Until August 2016, the term "academic fraud" wasn't even found anywhere in the NCAA bylaws.

Member-legislated changes went into effect in 2016 that included several substantive bylaw changes, including this addition:

The new Bylaw 14.02 doesn't tell us what the NCAA thinks "academic fraud" is; only that it's one example of academic misconduct, and that either student-athlete or institutional staff members can commit it. One thing seems certain to me though: there is nothing in the Bylaws to suggest that the NCAA sees any distinction between "a normal person's standards" of what is "academic fraud" and how the NCAA defines it, as Cunningham claimed.

Index

1. How the NCAA Defines Academic Fraud

2. The NCAA Bylaw that Covers Academic Fraud

3. NCAA's "Prior Determination"

4. Academic Fraud Post-Wainstein

5. NCAA Allegations Post-Wainstein

6. UNC's Strategy

1. How the NCAA Defines Academic Fraud

In actuality, the NCAA intentionally avoids defining academic fraud. You could say, defining academic fraud is not in its "wheelhouse." The responsibility for determining if conduct is academic fraud belongs primarily to the institution and it accrediting agency. The NCAA reinforced this principle in 2014 when the NCAA's Division I Legislative Council clarified for NCAA members that:"academic standards and policies governing misconduct are the responsibility of individual schools and their accreditation body." [Link]Not only does the NCAA defer determining what is or isn't academic fraud to the institution, but it also expects the institution "to make sure the case is handled according to policies applicable to all students."

So if UNC admits that what was discovered in its African and African-American (AFAM) Studies department was academic fraud, then the NCAA can accept that and apply that concession to its rules, and doesn't need to reinterpret it according to some non-specified, alternate, narrower definition to which Cunningham enigmatically refers.

2. The NCAA Bylaw that Covers Academic Fraud

Prior to a 2016 rule change, the way the NCAA enforced breaches of its academic misconduct bylaws by institutional staff members (that affected student-athletes) was through the "arranging for fraudulent academic credit" part of Bylaw 10.1:Bylaw 10.1-(b):

"Unethical conduct by…a current or former institutional staff member, may include, but is not limited to…knowing involvement in arranging for fraudulent academic credit…for a prospective or an enrolled student-athlete."

The NCAA used that rule to charge a UNC tutor and several football players with academic fraud in 2011. UNC didn't contest the academic fraud charge in that case and the school was sanctioned in March 2012.

The AFAM academic scandal was uncovered in August 2011 as the previous infractions case was in the later stages of investigation and approaching the hearing phase. A UNC internal working group (Jack Evans, Jonathan Hartlyn and Leslie Strohm), along with NCAA investigators (Mike Zonder and Chance Miller), looked into the issues, interviewed students and staff, including Dr. Julius Nyang'oro, examined documents, and ultimately determined that no additional allegations needed to be added to the existing charges at that time.

It was up to UNC to determine whether or not the conduct discovered in 2011 had constituted academic fraud. But since "no instance was found of a student receiving a grade who had not submitted written work" and UNC didn't, at that point, assess the issue as being academic fraud by institutional staff, the NCAA enforcement staff accepted that. There's no indication that UNC informed the NCAA that Crowder's grading of papers violated UNC policy. UNC certainly did not react with the same alarm then as it would when the details of Crowder and Nyang'oro's misconduct was reported by Kenneth Wainstein, three years later.

3. NCAA's "Prior Determination"

UNC has been trying to leverage the fact that, several times from 2011 to 2013, the NCAA enforcement staff had determined that it found no Bylaw violations in what had transpired at UNC. The focus of these arguments has mainly been on the charging of Bylaw 16 "Extra Benefits" infractions, which is a separate issue from the subject of this article.

But one of the instances UNC has highlighted was the discovery of 2013 internal email communication between Enforcement and Academic & Membership Affairs (AMA) staff that specifically addressed the application of Bylaw 10.1.

Neither the May 2012 Hartlyn-Andrews internal review nor the December 2012 Martin Report identified the breaches of UNC's academic policy that had been committed by Nyang'oro and Crowder. So when NCAA enforcement's Mike Zonder asked the NCAA's Academic & Membership Affairs (AMA) staff to weigh in on whether the Martin Report revealed any NCAA bylaw violations, the conclusion, according to AMA staffer Steve Mallonee, was he saw nothing in that report that would indicate a breach of Bylaw 10.1.

Mallonee responded as follows (highlights and annotation added by me):

Mallonee's reference reconfirms how it is the institution's responsibility to report a violation of 10.1-(b) if an "institutional staff member...is knowingly involved in arranging fraudulent academic credit...for a[n]...enrolled student-athlete..."

This is not the same as the institution reporting information and expecting the NCAA to decipher if a violation has occurred. The onus is not on the NCAA to make that determination for the school. The institution must apply its own standards and policies to determine if the misconduct was academic misconduct. If so, and if student-athletes were affected, it's incumbent upon the institution to report it to the NCAA; not for the institution to rely on an AMA/Enforcement staff judgment.

The University held no one accountable for academic misconduct in the wake of Hartlyn-Andrews or Martin investigations. UNC's accrediting agency, the Southern Association of Colleges & Schools, Commission on Colleges (SACSCOC), completed a review in 2013 and did not admonish UNC for academic policy failures. Nyang'oro had been forced to resign, but that was ostensibly for his negligence and possible criminal fraud for having collected payment for courses he hadn't actually taught. Crowder had already retired in 2009, but UNC stopped short of deeming her conduct academic fraud. Instead, her actions were, like the courses themselves, euphemistically called "irregular" and "aberrant."

Mallonee stated that "there is nothing definitive in the [Martin] report" to substantiate a 10.1-(b) infraction; which is true. The Martin Report didn't address Deborah Crowder having graded work that resulted in academic credit being awarded, despite her not having the authority to do so. So, since UNC hadn't policy violation facts and never deemed the behavior to have been academic fraud, the NCAA affirmed that violation of 10.1-(b) hadn't been substantiated.

Note, however, that Mallonee did provide the 2000 interpretation of 10.1-(b) that explained how a finding of academic fraud could be substantiated, even if there had been no "systematic effort to benefit student-athletes in general." In other words, it wouldn't matter what Crowder or Nyang'oro's motives were or whether or not non-athletes benefited as much as athletes. In terms of 10.1-(b), if institutional academic misconduct had an impact on a single, unwitting student-athlete, 10.1-(b) would be applicable.

4. Academic Fraud Post-Wainstein

The Wainstein Report was different from the previous UNC-chartered reviews in at least one key way. One of the findings was that students had received grades and credit for courses in which Deborah Crowder had performed functions reserved for faculty, in violation of University policy. Her motives don't matter. Crowder had "arranged for fraudulent academic credit."Now, some UNC defenders have said that, because UNC has never altered any student transcripts or discredited any prior courses, those courses, while deficient, remain "legitimate." This is specious, because the rationale for academic fraud isn't based on whether or not the university de-legitimizes past courses or previously awarded credit. A school policy of "sealing" transcripts after year doesn't inoculate against prior academic fraud simply by the fact the course credits can't be overturned for administrative reasons. Academic fraud still happened, and UNC, in a rare example of true contrition, agreed:

For the first time, on January 12th, 2015 -- three years and five months after the discovery of the AFAM academic misconduct -- UNC finally admitted what happened was academic fraud. It's probably the only time UNC has explicitly said so; although by its actions it has implicitly conceded the fact. If you believe Bubba Cunningham, this "academic fraud" is the "normal person's standard" of academic fraud, and that the NCAA has some other definition, distinct from this University admission.

But as shown, the NCAA doesn't have its own definition. Academic fraud is defined by the university, and in the wake of the Wainstein Report -- unlike after the Martin Report or the Hartlyn-Andrews Report or the very early on join UNC internal working group/NCAA investigation -- UNC had agreed it was academic fraud.

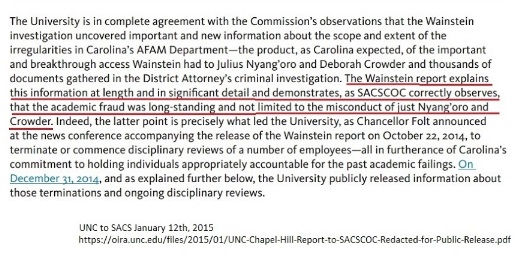

UNC acted on the findings of the Wainstein Report as if they were were shocking revelations. It agreed with SACSCOC that "the Wainstein investigation uncovered important and new information about the scope and extent of the irregularities in Carolina's AFAM Department."

UNC fired personnel on the basis of Wainstein:

More clearly than any prior review or investigation, Wainstein's investigation revealed just how Crowder had "knowing involvement in arranging for fraudulent academic credit…[for] enrolled student-athlete[s]."

Recall AMA's Mallonee's comment from earlier:

"The current 2000 official interpretation…does remain applicable to each individual student-athlete's situation and obviously could result in a finding of academic fraud, notwithstanding the lack of any systematic effort to benefit student-athletes in general."For NCAA bylaw 10.1-(b), it doesn't matter if non-students "benefited" as well. It doesn't even matter if the Crowder's intentions were honorable or if there was no "systematic effort to benefit student-athletes." If the institution considered her actions to be academic fraud, even if by no other means than awarding grades in violation of UNC policy, 10.1-(b) is violated.

Not only that, but UNC agreed with SACSCOC that the academic fraud was "not limited to the misconduct of just Nyang'oro and Crowder." Counselors on the ASPSA staff were fired for knowing that Crowder had been grading the papers and having exploited her fraud.

(This was a main point and objection brought forth in Bradley Bethel's film "Unverified," which took the University of North Carolina school system to task for firing "low-level" employees for something they had believed was condoned by senior faculty and leadership.)

Among the Exhibits supporting this finding was counseling staff Amy Kleissler's notice to athletes in 2009 that had been attached to email from Academic Support Program for Student-Athletes (ASPSA) counselor Beth Bridger to colleagues Cynthia Reynolds and Jaimie Lee:

The Wainstein Report forced a change in UNC's perspective, understanding and stance on the AFAM academic scandal. This, in turn, affected the NCAA case as well, though UNC has since sought to segregate NCAA issues from how it responded to Wainstein in answering its own institutional concerns; but in terms of Bylaw 10.1-(b), the issue of "academic fraud" is inextricably linked.

5. NCAA Allegations Post-Wainstein

In seeming contradiction to the foregoing argument, none of the alleged infractions in any of the three iterations of Notice of Allegations issued in the pending UNC case have used the phrase "academic fraud."

- Notice of Allegations (NOA) May 2015

- 1st Amended Notice of Allegations (ANOA) April 2016

- 2nd Amended Notice of Allegations (2ANOA) December 2016

UNC agreed back then that Wiley's actions violated Bylaw 10.1-(b) and constituted "academic fraud." UNC has not been so conciliatory this time.

But though the allegations don't explicitly specify "academic fraud," the fact that Allegation 1 in the 2ANOA cites Bylaw 10.1 means that "academic fraud" is, indeed, in play.

Allegation 1 has two parts:

- The second part -- allegation 1b -- doesn't address academic misconduct. Its focus is on violations of Bylaw 16.11.2.1 (Extra Benefits), and the subjects of that allegation are the institution as a whole and the athletics department. Even though UNC admitted the academic fraud was "not limited to the misconduct of just Nyang'oro and Crowder," UNC has not self-reported nor has Enforcement alleged Bylaw 10.1 violations as it pertains to the counseling staff or other institution members.

- Allegation 1a is where Bylaw 10 (Ethical Misconduct) is cited. UNC did not self-report this infraction, but the Enforcement staff added it in the third version of the allegations. Its focus is on the misconduct of Dr. Nyang'oro and Ms. Crowder.

It'll be the Committee on Infractions (COI) hearing panel's task to determine if any violations of Bylaw 10.1 are substantiated by the facts. Though not directly applicable in UNC's case, the rational for the 2016 Bylaw changes may illustrate the NCAA membership's thinking as to when it considers "academic misconduct involving student-athletes [to fall] within the purview of the NCAA and when academic misconduct should be an institutional matter." [link]

Side Note: Often lost on people is the fact that this pending UNC infractions case doesn't allege any misconduct by student-athletes. In many NCAA academic misconduct cases, the phrase "involving student-athletes" suggests a student-athlete must be a party to the misconduct. That's not true. The alleged academic misconduct in this case is limited to institutional staff members. As we've been continually reminded by UNC, the students "did the work" that was assigned to them. It's the conduct of faculty and staff that is subject to Bylaw 10.1 scrutiny in the allegations.

Even though it is not alleged, the hearing panel could also find that allegation 1a (ASPSA staff) and allegation 2 (Crowder's improper assistance) substantiate violation of Bylaw 10.1 as well.

6. UNC's Strategy

UNC never self-reported a 10.1 violation in this case. To the contrary, UNC has resisted connecting its concession to SACS with the NCAA case. Even the firing of counselors Bridger, Lee and Blanton has been ambiguously suggested as having been for reasons other than "the conduct asserted" in NCAA's allegations:UNC's NCAA defense team has tried to counter the NCAA Enforcement staffs allegations by claiming that the investigators who were party to the 2011 initial investigation were privy to all the material aspects of the scandal way back in 2011, and that the Wainstein Report shed no new light on the situation as far as NCAA issues were concerned. That's fascinating, given the administration's expressions of shock over learning just how beyond her authority Crowder had gone, and considering the actions UNC took with regard to what Wainstein found about the extent to which others were aware of Crowder's misconduct.

For example, one piece of evidence that surfaced in the Wainstein Report was the July 2009 Bridger email with the Kleissler attachment previously mentioned. (see above)

Two years after the release of the Wainstein Report, UNC's lawyer in NCAA matters, Rick Evrard, wrote a letter to the NCAA director of Enforcement, reminding him that Kleissler's note had been discovered by UNC in 2011 and had been disclosed to the NCAA in Aug/Sep 2011. This was one of several items Evrard points out in an attempt to convince NCAA enforcement that Wainstein's information wasn't "new":

But if it wasn't new to NCAA investigators, then the fact that Crowder had been grading papers and acting like faculty, in violation of UNC's policy, wasn't new to UNC either, and UNC had known that since 2011 yet didn't self-report it. Not only did it not self-report it to the NCAA, but it didn't report it to the SACSCOC special committee reviewing UNC in 2013.

Who's "wheelhouse" is it to assess if such conduct is a violation of institution policy? If UNC wasn't alarmed by the fact that Crowder was doing the grading in 2011, then why should UNC expect the NCAA enforcement staff to figure out that Crowder was non-faculty and that that would render her actions as violation of 10.1-(b)? This wasn't a self-evident situation like a tutor providing too much assistance on a paper. (Even that is not for the NCAA to decide if the institution wants to claim that the level of tutor "help" is appropriate.) Neither the NCAA enforcement staff, nor the AMA, would have understood the ramifications of the situation until UNC and SACSCOC reacted to the Wainstein Report.

It was, and is, the institution's responsibility to define, identify and report academic fraud. If that academic fraud impacts student-athletes, then it is reportable to the NCAA. UNC failed to do so.

Even worse, UNC has sought to obfuscate the matter and characterize it as Enforcement's failure.

Not only that, but incredibly, UNC STILL seems to insist that the Enforcement and AMA staff's previous determination prior to Wainstein was correct and that there was no academic fraud per "NCAA's definition."

Quite to the contrary: it was always academic fraud and the previous determinations were flawed and incorrect. Now, belatedly, the NCAA staff has gotten it right.

Who's "wheelhouse" is it to assess if such conduct is a violation of institution policy? If UNC wasn't alarmed by the fact that Crowder was doing the grading in 2011, then why should UNC expect the NCAA enforcement staff to figure out that Crowder was non-faculty and that that would render her actions as violation of 10.1-(b)? This wasn't a self-evident situation like a tutor providing too much assistance on a paper. (Even that is not for the NCAA to decide if the institution wants to claim that the level of tutor "help" is appropriate.) Neither the NCAA enforcement staff, nor the AMA, would have understood the ramifications of the situation until UNC and SACSCOC reacted to the Wainstein Report.

It was, and is, the institution's responsibility to define, identify and report academic fraud. If that academic fraud impacts student-athletes, then it is reportable to the NCAA. UNC failed to do so.

Even worse, UNC has sought to obfuscate the matter and characterize it as Enforcement's failure.

Not only that, but incredibly, UNC STILL seems to insist that the Enforcement and AMA staff's previous determination prior to Wainstein was correct and that there was no academic fraud per "NCAA's definition."

Quite to the contrary: it was always academic fraud and the previous determinations were flawed and incorrect. Now, belatedly, the NCAA staff has gotten it right.

Note:

The June 24th, 2009 email from Bridger to Reynolds and Lee with Kleissler's notice to student-athletes was not included among the Factual Items (FIs) of either of the first two NOAs. It was cited by NCAA Enforcement in its August 19th, 2016 reply to UNC's August 1st, 2016 Response to the NOA. UNC sought to leverage Enforcement's citation of that document as additional proof that the NCAA knew all the material aspects of the "academic fraud" in 2011 when it chose not add the allegation to the 2012 case.

Kleissler's note affirming knowledge that Crowder was grading papers has now been added to the 2ANOA (which now alleges bylaw 10.1 violation) as FI No.126, in support of Allegation 1 (Unethical Conduct) and Allegation 5 (Lack of Institutional Control).